Viewstamped Replication is one of the earliest consensus algorithms for distributed systems. It is designed around the log replication concept of state machines and it can be efficiently implemented for modern systems. The revisited version of the paper offers a number of improvements to the algorithm from the original paper which both: simplifies it and makes it more suitable for high volume systems. The original paper was published in 1988 which is ten years before the Paxos algorithm 1 was published.

I will explain how the protocol works in detail covering as well a number of optimizations which are described in the papers. The “revisited” version offers a simplified version of the protocol with improvements which were made by the authors in later works and published after the original paper. Therefore most of the content here will be driven from the more 2012 paper.

- Paper links:

- Viewstamped Replication: A New Primary Copy method to Support Highly-Available Distributed Systems, B. Oki, B. Liskov, (1988) 2

http://pmg.csail.mit.edu/papers/vr.pdf - Viewstamped Replication Revisited, B. Liskov, J.Cowling (2012) 3

http://pmg.csail.mit.edu/papers/vr-revisited.pdf - Viewstamped Replication presentation at PapersWeLove London 4

- Viewstamped Replication: A New Primary Copy method to Support Highly-Available Distributed Systems, B. Oki, B. Liskov, (1988) 2

What is “Viewstamped Replication”?

It is a replication protocol. It aims to guarantee a consistent view over replicated data. And it is a “consensus algorithm”. To provide a consistent view over replicated data, replicas must agree on the replicated state.

It is designed to be a pluggable protocol which works on the communication layer between the clients and the servers and between the servers themselves. The idea is that you can take a non-distributed system and using this replication protocol you can turn a single node system into a high-available, fault-tolerant distributed system.

To achieve fault-tolerance, the system must introduce redundancy in time and space. Redundancy in time is to combat the unreliability of the network. Messages can be dropped, reordered or arbitrarily delayed, therefore protocol must account for it and allow requests to be replayed if necessary without causing duplication in the system. Redundancy in space is generally achieved via adding redundant copies in different machines with different fault-domain isolation. the aim is to be able to stay in operation in face of a node failure, whether is a system crash or a hardware failure, the system must be able to continue normal operation within certain limits.

Together, the redundancy in time and space provide the ability to tolerate and recover from temporary network partitions, systems crashes, hardware failure and a wide range of network related issues.

However, the system can only tolerate a number of failures depending on

the cluster (or ensemble size). In particular to tolerate 𝑓

failures it requires an ensemble of 2𝑓 + 1 replicas. The type of

failures that the protocol can tolerate are non-Byzantine failures 5

which means that all the nodes in the ensemble will be either in a

working state, or in a failed state or simply isolated. However, every

node in the system will not deviate from the protocol and it will not

lie about its state. Therefore, if the system must be able to tolerate

one node to be unresponsive, then the minimum ensemble size is 3

nodes. If the system must be able to tolerate 2 concurrent failures,

then the minimum size of the cluster required is 5 nodes, and so

on. 𝑓 + 1 nodes is called quorum. It is not possible to create a

quorum with less than 3 nodes, therefore the minimum ensemble size is

3.

Replicated State Machines

Viewstamped Replication is based on the State Machine Replication concept 6. A State Machine has an initial state and an operation log. The idea is that if you apply the ordered set of operation in the operation log to the initial state you will end up always with the same final state, given that all the operations in the operation log are deterministic.

Therefore, if we replicate the initial state and the operation log into other machines and repeat the same operations the final state on all the machines will be the same.

It is crucial that the order of operations is preserved as operations are not required to be commutative. Additionally all sources of indeterminism must be eliminated before the operation is added to the operation log. For example, if you have an operation which generate a unique random id, the primary replica will need to generate the random id and then add an operation in the log which already contains the generated number such that when the replicas apply the operation won’t need to generate the random unique id themselves which will cause the replica state to diverge.

The objective of Viewstamped Replication is to ensure that there is a strictly consistent view on the operation log. In other words, is ensures that all replicas agree on which operations are in the log and their exact order.

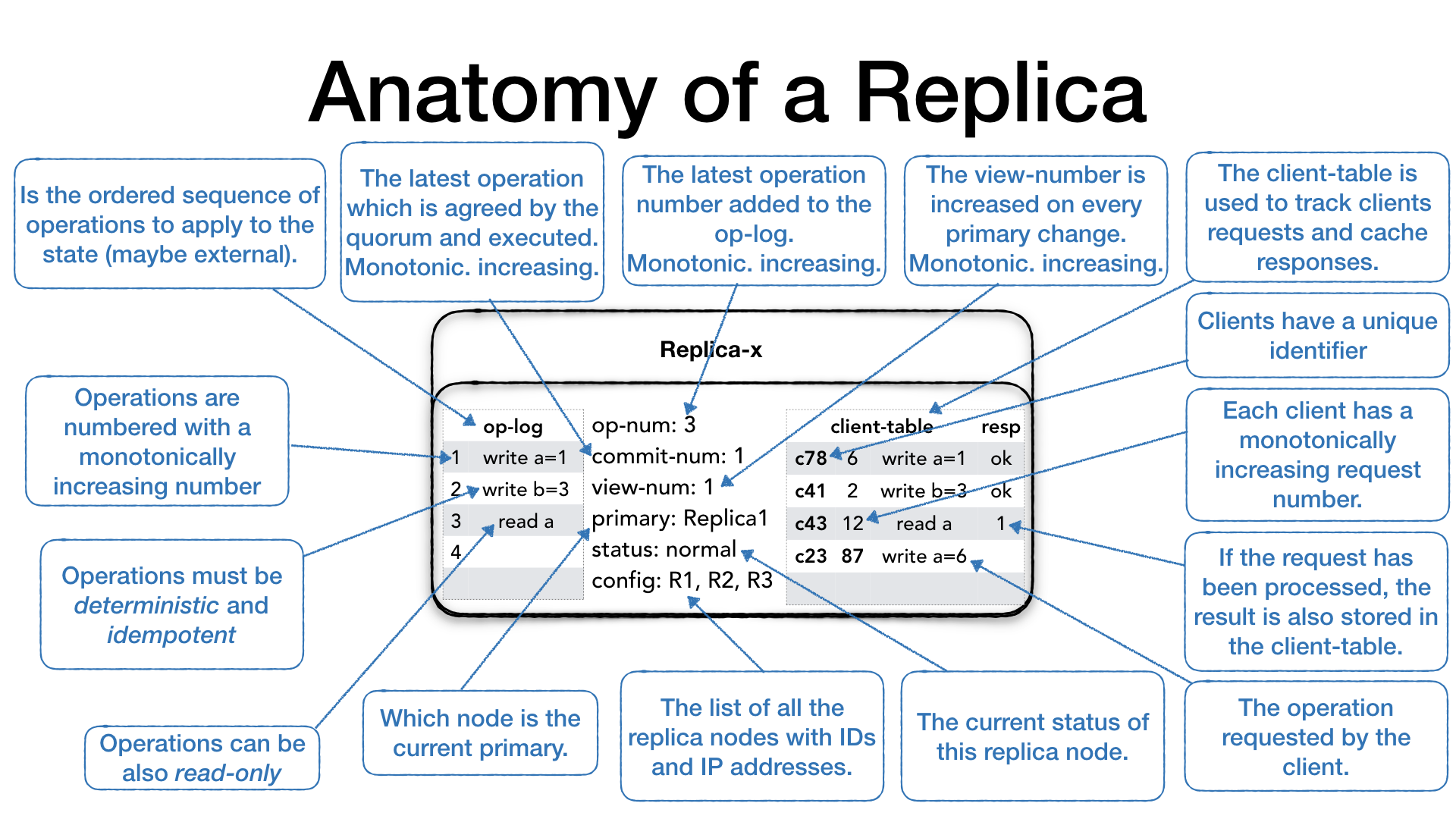

Anatomy of a Replica

The ensemble or cluster is made of replica nodes. Each replica is composed of the following parts.

The operation log (op-log) is a (mostly) append-only sequence of

operations. Operations are applied against the current state which

could be external to the replica itself. Operations must be

deterministic which means that every application of the same

operation with the same arguments must produce the same

result. Additionally, if the operations produce side effect or write

to an external system you have to ensure the operation is applied only

once by the use of transactional support or by making operation

idempotent so that multiple application of the same operation won’t

produce duplication in the target system. Each operation in the

operation-log has a positional identifier which is a monotonically

increasing number.

The last inserted operation number is the high water mark for the operation

log and it is recorded as the op-num which is a monotonically

increasing number as well. It identifies which operation has been

already received and it is used in parts of the protocol.

Operations in the op-log are appended first, then shared with other

replicas and once there is a confirmation that enough replicas have

received the operation then it is actually executed. We will see how

this process works in more details later. The commit-num represents

the number of the last operation which was executed in the replica. It

also implies that all the previous operations have been executed as

well. commit-num is a monotonically increasing number.

The view-number (view-num) is a monotonically increasing number

which changes every time there is a change of primary replica in

the ensemble.

Each replica must also know who the current primary replica is.

This is stored in the primary field.

The status field shows the current replica operation mode.

As we will see later, the status can assume different values

depending on whether the replica is ready to process client requests,

or it is getting ready and doing internal preparation.

Every replica node will also have a list of all the replica nodes in the ensemble with their IP addresses and their unique identifiers. Some parts of the protocol require the replicas to communicate with other replicas therefore they must know how to contact the other nodes.

The client-table is used to keep track of client’s requests.

Clients are identified by a unique id, and each client can only make

one request at the time. Since communication is assumed to be

unreliable, clients can re-issue the last request without the risk of

duplication in the system. Every client request has a monotonically

increasing number which identifies the request of a particular

client. Each time the primary receives a client requests it add the

request to the client table. If the client re-sends the same requests

because didn’t receive the response the primary can verify that the

request was already processed and send the cached response.

For brevity, the pictures which will follow will omit some details.

The Protocol

Next, we are going to analyse the protocol in details. The protocol is presented in the paper in its simplest form first. Then the paper goes on describing a number of optimisations which do not change the basic structure of the protocol but make it efficient and practical to implement for real-world application. Efficiency is a major concern throughout both papers as the authors were building real-world systems.

Client requests handling

In this section, we are going to see how a client request is processed and the data replicated. We are going to see, in details, how the protocol ensures that at least a quorum of replicas acknowledges the request before executing the request.

Clients have a unique identifier (client-id), and they communicate

only with the primary. If a client contacts a replica which is not the

primary, the replica drops the requests and returns an error message

to the client advising it to connect to the primary. Each client can

only send one request at the time, and each request has a request

number (request#) which is a monotonically increasing number. The

client prepares <REQUEST> message which contains the client-id,

the request request# and the operation (op) to perform.

The primary only processes the requests if its status is normal,

otherwise, it drops the request and sends an error message to the client

advising to try later. When the primary receives the request from the

client, it checks whether the request is already present in the client

table. If the request’s number is greater of the one in the client

table then it is a new request, otherwise, it means that the client

might not have received last response and it is re-sending the

previous request. In this case, the request is dropped and the primary

re-send last response present in the client table.

If it is a new request, then the primary increases the operation

number (op-num), it appends the requested operation to its operation

log (op-log) and it updates the client-table with the new request.

Then it needs to notify all the replicas about the new request, so it

creates a <PREPARE> message which contains: the current view number

(view-num), the operation’s op-num, the last commit number

(commit-num), and the message which is the client request itself,

and it sends the message to all the replicas.

When a replica receives a <PREPARE> request, it first checks whether

the view number is the same view-num, if its view number is

different than the message view-num it means that a new primary was

nominated and, depending on who is behind, it needs to get up to date.

If its view-number is smaller than the message view-num, then it

means that this particular node is behind, so it needs to change its

status to recovery and initiate a state transfer from the new

primary (we will see the primary change process called view change

later). If its view-number is greater than the message view-num,

then it means that the other replica needs to get up-to-date, so it

drops the message. Finally, if the view-num is the same, then it

looks at the op-num in the message. The op-num needs to be

strictly consecutive. If there are gaps it means that this replica

missed one or more <PREPARE> messages, so it drops the message and

it initiates a recovery with a state transfer. If the op-num is

strictly consecutive then it increments its op-num, appends the

operation to the op-log and updates the client table.

Now the replica sends an acknowledgment to the primary that the

operation, and all previous operations, were successfully prepared. It

creates a <PREPARE-OK> message with its view-num, the op-num and

its identity. Sending a <PREPARE-OK> for a given op-num means

that all the previous operations in the log have been prepared as well

(no gaps).

The primary waits for 𝑓 + 1 including itself <PREPARE-OK>

messages, at which point it knows that a quorum of nodes knows

about the operation to perform therefore it is considered safe to

proceed as it is guaranteed that the operation will survive the loss

of 𝑓 nodes. When it receives enough <PREPARE-OK> then it performs

the operation, possibly with side effect, it increases its commit

number commit-num, and update the client table with the operation

result. Again, advancing the commit-num must be done in strict order,

and it also means that all previous operations have been committed

as well.

Finally, it prepares a <REPLY> message with the current view-num

the client request number request# and the operation result

(response) and it sends it to the client.

At this point, the primary is the only node that has performed the

operation (and advanced its commit-num) while the replicas have only

prepared the operation but not applied. Before they can safely apply

they need confirmation from the primary that it is safe to do so.

This can happen in two ways.

Let’s assume that the same client or a new client comes along and

makes a new request. The client will create a <REQUEST> message and

send it to the primary as well. The primary will process the request

as usual, check the client table, increase the op-num and append to

the op-log, then it creates a <PREPARE> message with the

view-num, the op-num, the client’s message but it also includes

its commit-num which now shows that the primary advanced its

position.

When the replicas receives the <PREPARE> it follows the normal

process; It checks the view-num, checks the op-num, increment its

operation number append to the op-log and update the client table,

then it sends a <PREPARE-OK> to the primary for the operation it

received.

However, the <PREPARE> message from the primary also contained the

commit-num which showed that the primary has now executed the

operation against its state and it is notifying the replicas that it

is safe to do so as well. So the replicas will perform all requests in

their op-log between the last commit-num and the commit-num in

the <PREPARE> message strictly following the order of operations

and advance its commit-num as well. At this point both, primary and

replicas have performed the committed operations in their state.

So we seen how the primary uses the <PREPARE> message to inform

replicas about new operations as well as operations which are now safe

to perform. But what if there is not a new request coming in? what if

the system is experiencing a low request rate, maybe because it is the

middle of the night and all users are asleep? If the primary doesn’t

receive a new client request within a certain time then it will create

a <COMMIT> message to inform replicas about which operations can now

be performed.

The <COMMIT> message will only contain the current view number

(view-num) and the last committed operation (commit-num). When a

replica receives a <COMMIT> it will execute all operation in their

op-log between the last commit-num and the commit-num in the

<COMMIT> message strictly following the order of operations and

advance its commit-num as well.

The <PREPARE> message together with the <COMMIT> message act as a

sort of heartbeat for the primary. Replicas use this to identify when

a primary might be dead and elect a new primary. This process is

called view change and it is what we are going to discuss next.

View change protocol

The view change protocol is used when one of the replicas detects that the current primary is unavailable and it proceeds to inform the rest of the ensemble. If a quorum of nodes agrees then the ensemble will transition to a new primary. This part of the protocol ensures that the new primary has all the latest information to act as the new leader.

Leader “selection”

In my view, one of the most interesting parts of the ViewStamped Replication protocol is the way the new primary node is selected. Other consensus protocols (such as Paxos and Raft) have a rather sophisticated way to elect a new primary (or leader) with candidates having to step up, ask for votes, ballots, turns etc. ViewStamped Replication takes a completely different approach. It uses a deterministic function over a fixed property of the replica nodes, something like a unique identifier or IP address.

For example, if the replica nodes IP addresses don’t change you could

use the sort function which given a list of nodes IPs will return a

deterministic sequence of nodes. The ViewStamped Replication

algorithm simply uses the sorted list of IPs to determine who is the

next primary node, and in round-robin fashion all nodes will, in

turn, become the new primary when the previous one is unavailable. I

find this strategy very simple and effective. There is no vote to

cast, candidates stepping up, election turns, ballots, just a

predefined sequence of who’s turn is.

For example, if you have a three nodes cluster with the following IP addresses

10.5.3.12 10.5.1.20 (1)

10.5.1.20 ~sort~> 10.5.2.28 (2)

10.5.2.28 10.5.3.12 (3)

The node 10.5.1.20 will be the first primary, and

everybody knows that it will be the first. When that node dies or is

partitioned away from the rest of the cluster, the next node to become

the primary will be the 10.5.2.28 followed by 10.5.3.12 and then

starting from the beginning again.

The protocol ensures that if the node who is set to be the next primary, somehow, has fallen behind and it is not the most up-to-date, it will be able to gather the latest information from the other nodes and get ready for the job. We will see this in more details in this section.

The view change

Let’s start with a working cluster. Replicas R1 to R5 are all up

and running, R1 is the first primary node, followed by R2 and so

on. Since ensembles are formed by 2𝑓 + 1 nodes, this cluster can

survive and continue processing requests in the face of two failed

nodes.

R1 is currently accepting client’s requests and those are handled as

seen earlier. Therefore for each client request, a <PREPARE> message

is sent to all replicas and they reply with a

<PREPARE-OK>. <COMMIT> messages are also used to signal which

operations are committed by the primary.

Let’s assume that the primary R1 crashes or is isolated from the

rest of the cluster. No more <PREPARE> or <COMMIT> messages will

be received by the rest of the cluster. As said previously these messages act as a heartbeat for the primary health.

At some point, in one of the nodes (R4 for example) a timeout will

expire, and it will detect that it didn’t hear from the primary since

a predefined amount of time. At this point the replica will change

its status to view-change, increase its view number (view-num)

and create a <START-VIEW-CHANGE> message with the new view-num and

its identity. It will then send this message to all the replicas.

When the other replicas receive a <START-VIEW-CHANGE> message with a

view-num bigger than the one they have, they set their status to

view-change and set the view-num to the view number in the message

and reply with <START-VIEW-CHANGE> to all replicas.

When a replica receives 𝑓 + 1 (including itself)

<START-VIEW-CHANGE> message with its view-num then it means that

the majority of the nodes agrees on the view change so it sends a

<DO-VIEW-CHANGE> to the new primary (selected as described above).

The <DO-VIEW-CHANGE> message contains the new view-num the last

view number in which the state was normal old-view-number, its

op-num and its operation log (op-log) and its commit number

(commit-num).

When the new primary, in this case, node R2, it receives 𝑓 + 1

(including itself) <DO-VIEW-CHANGE> with the same view-num it

compares the messages against its own information and pick the most

up-to-date. It will set the view-num the new view-num, it will

take the operation log (op-log) from the replicas with the highest

old-view-number. If many replicas have the same old-view-number it

will pick the one with the largest op-log, it will take the op-num

from the chosen op-log and the highest commit-num and execute all

committed operations in the operation log between its old commit-num

value and the new commit-num value. At this point, the new primary

is ready to accept requests from the client so it sets its status to

normal. Finally, it sends a <START-VIEW> message to all replicas

with the new view-num, the most up to date op-log, the

corresponding op-num and the highest commit-num.

When the other replicas receive the <START-VIEW> message they

replace their own local information with the data in the

<START-VIEW> message, specifically they take: the op-log, the

op-num and the view-num. They change their status to normal

and they execute all the operation from their old commit-num to the

new commit-num and they send a <PREPARE-OK> for all operation in

the op-log which haven’t been committed yet.

Some time later the failed node (R1) might come back alive either

because the partition is now terminated or because the crashed nodes

it has been restarted. At this point, the R1 might still think it is

the primary and be waiting for requests from clients. However, since

the ensemble transitioned to a new primary in the meantime, it is

likely that clients will be sending requests to the new primary and it

is likely that the new primary is sending <PREPARE>/<COMMIT>

messages to all the replicas, including the one which previously

failed. At this point, the failed replica will notice that

<PREPARE>/<COMMIT> messages have a view-num greater than

its view-num and it will understand that the cluster transitioned to

a new primary and that it needs to get up to date.

In this case, it will set its status to recovery and issue a

<GET-STATE> request to any of the other replicas. The <GET-STATE>

will contains its current values of the view-num, op-num and

commit-num together with its identity. The <GET-STATE> message is

the same message used by the replicas to get up to date when the fall

behind. The replica who receives the <GET-STATE> message will only

respond if its status is normal.

If the view-num in the <GET-STATE> message is the same as its

view-num it means that the requesting node just fell behind, so it

will prepare a <NEW-STATE> message with its view-num, its

commit-num and its op-num and the portion of the op-log between

the op-num in the <GET-STATE> and its op-num.

If the view-num in the <GET-STATE> message is different, then it

means that the node was in a partition during a view change. In this

case it will prepare a <NEW-STATE> message with new view-num, its

commit-num and its op-num and the portion of the op-log between

the commit-num in the <GET-STATE> this time and its op-num, this

is because some operations in the minority group might not have

survived the view-change.

This is concludes the discussion about the ViewStamped Replication protocol. We seen how requests are handled in the normal case, and we have seen how the ensemble safely transition to a new primary in case it detects a failure or partition in the previous one. We also seen how the protocol design accounts for unreliable network and allows for any message to be dropped, delayed or reordered and still work correctly.

Protocol optimisations

Some of the limitations described earlier were imposed to allow to focus the discussion over the protocol correctness and clarity. In this section we’ll see how some of the optimisations proposed by the authors make this protocol not only realistic to implement for a real world system, but also efficient and practical.

Persistent state

While the protocol as described above doesn’t require the internal

replica state to be persisted to work properly you can store the state

in a durable storage to speed up crash recovery. In fact in a large

system the operation log (op-log) could become, over time, quite

large. It would be unreasonable and ineffective to keep the entire

operation log only in memory. Upon a crash, or when a replica is

restarted it will require to get a copy of the op-log from another

replica (via <GET-STATE>) and if the replica has to transfer

terabytes of data the operation could take a long time.

Storing the internal replica state into a durable storage can speed up

the recovery in the event the process is crashed or restarted. In

fact in this case, new replica process will only need to fetch the

tail of the operation log since its last committed operation

(commit-num).

Since the persistent state is not required to run the protocol

correctly, then the implementer can make design decisions based on the

efficient use of the storage. For example it could decide to fsyinc

only when there are enough changes to fill a buffer, as supposed to

fsync-ing on every request which it would be slow and inefficient.

Additionally the durability of the state could be managed completely

asynchronously from the protocol execution.

Witnesses

Running the protocol has a cost. As we seen the primary has to wait

for a quorum of nodes to respond on every <PREPARE> request before

executing the client request. In a large cluster, as the number of

nodes increases, it also increases the number of nodes that the

primary has to wait for a response and it increases the likelihood the

at one being slower and having to wait for longer. In such cases we

can divide the ensemble into active replicas and witness replicas.

Active replicas account for 𝑓 + 1 nodes which run the full protocol

and keep the state. The primary is always an active replica. The

remainder of the nodes are called witnesses and only participate to

the view changes and recovery.

Batching

In a high volume system there will be a huge number of <PREPARE>

messages flying around. To reduce the latency cost of running the

protocol the primary replica could batch a number of operation

before sending a <PREPARE> messages to the other replicas. In this

case the <PREPARE> messages will include all the operations in the

batch and the <PREPARE-OK> message will confirm that all

operations in the batch have been prepared. Several batching

strategies can be applied for example the primary could wait for at

most 20 milliseconds or when 50 operations have been batched or

whichever comes first, and then send the batch in a single <PREPARE>

message.

The same strategy could be applied on the client side for batching client’s requests, given that the client table is adjusted to accommodate a batch of requests.

Fast read-only requests on Primary

In the general definition of the protocol, read-only requests, which do not alter the state are served via the normal request processing. However since read requests do not need to survive a partition, they could be served unilaterally by the primary without contacting the other replicas.

The advantage of this optimisation is that read requests could benefit of shorter latency as there is no additional cost of running the protocol. However, in some case it is possible for the primary to serve stale responses. Let’s consider the following case:

An ensemble with three replica nodes (R1, R2, R3) and R2 is

the current primary. A bunch of clients are connected to the

primary and issuing requests. Requests manipulate a set of named

registers. The current value of the register a is 1. At a certain

point a partition occur which isolates the primary (R2) from the

rest of the ensemble and from most of the clients. Once the view

change protocol kicks in replica R3 will be elected as a new

primary, and clients will reconnect to the new primary.

At this point one of the clients could request a change of the

registry a = 2 and the change would succeed because a quorum of

replica nodes is available (R1 and R3).

In the meanwhile the old primary (R2) is unaware of the change to

the register a because the partition is still isolating

communications. Therefore is not even aware that a new primary

replica has been selected and it is no more the current primary.

An unfortunate client which is in the same side of the partition as

the old primary (R2) might still be able to talk to the old primary.

In this case if the client is requesting the current value of register

a, it will get a stale value.

To avoid this problem and make read-only requests possible to be served unilaterally by the primary we can make the use of leases. A primary can only serve read-only requests without running the protocol and consulting with the other replicas if and only if, its lease is not expired. When the lease expires, the primary must run the protocol and get the grant for a new lease which will ensure the view hasn’t changed in the meantime. In case of a partition, the ensemble will have to wait for the lease to expire before triggering a view-change and select a new primary.

Read-only requests on other replicas

In high request volume systems, where the number of read requests are much higher than the write requests, and if clients systems can accept stale reads (eventually consistent reads), then read-only requests can be made directly to the follower replicas. It is a effective way to reduce the load on the Primary and scale out the reads across all replicas. The primary is always handling the writes.

In this situations it might be useful to track causality of client

requests, for example a client makes a write followed by a read of the

same value (read your own writes). Causality can be achieved by

tracking the operation number op-num for a client write request and

propagating back this information to the client. Clients interested in

causal ordering can issue a read request to a follower replica stating

the op-num. In this case the replica knows that it must respond to

that request only after it advanced its commit-num past the

request’s op-num.

For example the client is connecting to the primary and ask for a

write operation such as a registry increment (write a = a + 1), the

primary will process the request as usual, but along with the response

it will communicate the operation number (op-num) for this request.

The client records the op-num and it uses to make subsequent

requests to the follower replicas for a read-only request. The replica,

if it hasn’t processed the operation in the client request op-num it

will have to wait until it the primary communicate that it is safe to

do so and then reply.

Ensemble reconfiguration

As seen so far, each node needs to be known to the others for the protocol to work correctly. However, modern systems, especially in a cloud environment, tend to change frequently their ensemble configuration. Maybe as a response to the increasing or decreasing of load (elastically scalable systems), or just as a consequence of operational necessities (hardware replacement, network reconfiguration etc).

To face this increasingly common requirement the authors proposed a protocol extension to allow a reconfiguration of the ensemble. With this extension is possible to add, remove, or replace some or all nodes. The only limit is that the minimum allowed number of nodes is three, below this limit is not possible to achieve a quorum.

In order to support reconfiguration the replicas have to track

additional properties. A monotonically increasing number called

epoch-num tracks every reconfiguration, a property called

old-config holds the previous configuration (list of nodes IPs,

names, and IDs). Finally a new status called transitioning is used

to mark when a reconfiguration is in progress.

A special client, typically with admin rights, will issue a

<RECONFIGURATION> request. The request includes the current

epoch-num, the client-id, the request# and the new-config with

the list of all ensemble nodes which is expected to replace the

current configuration.

The request will be sent to the primary and processed as a normal

request. However, as soon as a <RECONFIGURATION> request is

received by the primary it will stop accepting new client’s requests.

The other replicas will process the request as usual and send a

<PREPARE-OK> message back to the primary. Once the primary receives

a quorum of <PREPARE-OK> responses it will increase the epoch-num

and send a <COMMIT> message to all replicas. At this point it sends

a <START-EPOCH> to all new replicas (all the replicas which are part

of the new configuration but not of the old configuration) and it sets

the status = transitioning. The <START-EPOCH> contains the new

epoch-num the primary op-num and both: the old and new

configuration.

When the new replicas receive the <START-EPOCH> message they update

the configuration taking old-config and new-config from the

message itself, they reset the view-num to zero and set their

status = transitioning. If a new replica is missing data in

their op-log it will issue a <GET-STATE> request to the old

replicas. Once the new replica is up to date, then it sets its status

= normal, send a <EPOCH-STARTED> with the new epoch-num and its

identity to the old group, and finally, the new primary will start to

accept client requests.

This protocol extension allows to control the size of the ensemble for both: sizing up and sizing down. Additionally it can be used to replace a defective machine or also to migrate the entire cluster to a new set of more powerful machines.

Conclusions

As we seen the Viewstamped Replication algorithm is a fairly simple consensus algorithm and quite interesting replication protocol. It is quite simple to understand and, together with the many optimisations proposed, it can be implemented efficiently for real world application. Since it operates only on the interactions between replicas and clients it can be used as a “library” wrapper atop an existing system rendering the system distributed, high available and strictly consistent. For example it possible to take a single node file system and turn it into a distributed high available file system, which it was the initial motivation of the viewstamped replication protocol in first place. Moreover it could be used to wrap communications of systems such as Redis and Memcache or any other non-distributed system and turn it into a distributed, fault tolerant, high available and strictly consistent system.

Links and resources:

-

Paxos algorithm - The Part-Time Parliament, Leslie Lamport (1998) ↩

-

Viewstamped Replication: A New Primary Copy method to Support Highly-Available Distributed Systems, B. Oki, B. Liskov, (1988) ↩

-

Viewstamped Replication Revisited, B. Liskov, J.Cowling (2012) ↩

-

Viewstamped Replication presentation at PapersWeLove London ↩

-

Implementing Fault-Tolerant Services Using the State Machine Approach: A Tutorial, Schneider, Fred (1990) ↩